Our trip to the Caspian Sea was hastily arranged after Masoud received a phone call from his old friend Javod, whom he had been trying to contact for several weeks. Although previously a resident of Tehran for many years, unbeknownst to Masoud, he had recently moved back to Chaloos on the seacoast. The reasons for this move would become apparent later.

We pull away at 0718h, another crystal clear, beautiful day. It is 7 degrees Celsius. Two traffic police officers stand at a corner. These traffic officers seem to appear everywhere, but through my western eyes, don’t control anything. On this early morning during Narooz, we are on the four lane controlled access Niayish Highway. We continually pass buildings in various stages of construction.

The original plan was for five of us to take this journey, but Ahmed is sick and Maryam, Ali’s fiancée, has decided it would be unwise if she came. If stopped at a police checkpoint she is concerned about being challenged as an unmarried woman travelling with men with whom she is not related as defined by the Islamic Republic of Iran.

As the sun rises higher the dirty brown smudge of the Tehran air becomes more visible. By 0800h we have pulled off the main highway at Karaj. Before continuing, we stop for an oil change where David Beckham (or his card board cut out) sells his Castrol brand of service. The business owner cheerfully and briskly serves us, and in less than ten minutes our trip continues. If only I could count on this service from Canadian Tire.

This is regarded by many as the most beautiful of the highways to take you north to the Caspian Sea. We approach a large traffic circle where dozens of people stand, looking for a ride. As we push into the mountains small dilapidated square box residences seem to crawl up the slopes with us. We enter the first of a series of tunnels, signifying our departure from Karaj. This is a mountainous winding route. We follow a stream up the valley. Sheer cliffs  loom on either side. The road is busy, yet impatient drivers insist on attempting to pass. Overloaded vehicles crawling up the hill further reduces traffic speed while increasing everyone’s frustration level. Stone walls protect many of the roadside properties. Most of these walls are covered in painted advertising.

loom on either side. The road is busy, yet impatient drivers insist on attempting to pass. Overloaded vehicles crawling up the hill further reduces traffic speed while increasing everyone’s frustration level. Stone walls protect many of the roadside properties. Most of these walls are covered in painted advertising.

Garbage often litters the side of road and a dog is seen picking through it. An endless snake of vehicles proceeds up the mountain.

Cars continue to pass on corners as we wind our way up the hill. The police are maintaining a strong presence on this section of the road, and are actually pulling some wayward drivers over. A cruiser screams past us, hopefully in pursuit of a particularly offensive driver whom I witnessed force several vehicles off the road as he charged up the hill in his 30 year old Oldsmobile.

From the valley I look up and note at least four major switchbacks in the road as it makes its way up the mountain. The rock faces are sheer. It is a very long way to the bottom as I glance out of my window. It is the first time I have experienced my fear of heights from a car. I have never noticed so much tension in my body on a road trip as I am experiencing at this moment. With the treacherous road and the outrageous driving habits I feel every muscle flexing. I note the almost constant grip I have had on the “holy shit” handle above the passenger door.

The tunnels are lit, but the interior rock face is jagged, as they have not been lined with concrete. We have passed a large dam, and the headwater is to our left.

Families pull off on the side of the road, often cooking breakfast on an open-air fire. There is much evidence of recent rockslides. The headwater from the dam is now reduced to a fast flowing stream a few metres wide.

We pull into Gadchscar for a toilet break. The shaded ground is frozen, but mud is beginning to appear where the sun is shining. A police checkpoint is twenty metres ahead of where we stop. I observe them as they randomly motion oncoming traffic to pull over. We climb back into our vehicle and pull into traffic, but as soon as we approach the checkpoint we are ordered to the side of the road for inspection. The officer at the driver’s door demands my passport, while another officer opens my door. A brief discussion in Farsi ensues. It was later explained to me that the officer in temporary possession of my passport began to insist that I needed a permit to travel on this particular road. Masoud was able to deftly dissuade him of this opinion by pointing out that since I had a visa for Iran, and the road was in Iran, that I had all the permission I required. We continued on our journey.

We pull into Gadchscar for a toilet break. The shaded ground is frozen, but mud is beginning to appear where the sun is shining. A police checkpoint is twenty metres ahead of where we stop. I observe them as they randomly motion oncoming traffic to pull over. We climb back into our vehicle and pull into traffic, but as soon as we approach the checkpoint we are ordered to the side of the road for inspection. The officer at the driver’s door demands my passport, while another officer opens my door. A brief discussion in Farsi ensues. It was later explained to me that the officer in temporary possession of my passport began to insist that I needed a permit to travel on this particular road. Masoud was able to deftly dissuade him of this opinion by pointing out that since I had a visa for Iran, and the road was in Iran, that I had all the permission I required. We continued on our journey.

As we head to higher elevations snow banks are appearing, and looming larger. Travel is slow, barely exceeding 40 kph, as we follow two diesel belching Mercedes 0302 buses. Snow sheds are in place to protect from avalanche. We have travelled through the Kandovan tunnel to enter a completely snow covered environment.

This changes quickly though, as our elevation drops, and we head down to the Caspian Sea. Our first accident of the morning, with one vehicle nose first into a ditch and rock face, slows traffic temporarily.

We are now driving down a steep gorge, not much wider than the road itself. We enter Sizeh Bizesh. Roadside services selling souvenirs and various foodstuffs hug the cliff. Fresh meat hangs in the windows of several stores while a smoky haze hangs over the entire valley.

We have been on the road a few minutes short of 3 hours and have come 150 kms. Small rocks litter the road. We descend the mountain only meters behind a fully loaded pick up truck. Masoud constantly peers for an opportunity to pass. More than once he has attempted to respond to my concerns about this dangerous road. He is confident in his knowledge of this road and his skills. He even offers to turn back, probably noting a greying of my complexion with every twist and turn. I tell him that I won’t give up this experience that easily. Just then a car without headlights passes our line of vehicles through an unlit tunnel.

The trip through the gorge north from our tea break to Marzan Abad is relentless. It is the most dramatic highway I have ever experienced. The switchbacks are countless. Large rock faces hang over us. At times I feel that if I were permitted to stand in the middle of the road I could touch the gorge on either side.

The trip through the gorge north from our tea break to Marzan Abad is relentless. It is the most dramatic highway I have ever experienced. The switchbacks are countless. Large rock faces hang over us. At times I feel that if I were permitted to stand in the middle of the road I could touch the gorge on either side.

For the second day of travel I am observing the world from the front passenger seat. Yesterday Faraj sat in the back. Today it is Ali occupying that spot. Perhaps out of a need to care for both the driver and the foreign visitor, both of them seem compelled to feed us. There is a steady stream of peeled apples and oranges, nuts and the occasional zucchini. Although well intentioned, it magnifies my apprehension as I travel this road and watch Masoud expertly thread our car through the available space while removing excess orange seeds, apple cores, pistachio shells and zucchini stems from his hand.

Another component of driving in Iran is that you are constantly being pleaded with by roadside vendors to buy their wares. People stand by the side of the road waving oranges, bananas, bottles of refreshment, and anything else they think they may entice you with. They are just as pervasive on this mountain road as they are on an expressway. They are not so much the danger, as are the purchasers, as they are prone to sudden stops, or driving at you from the opposite side of the road to negotiate for the bargain they have eyed.

Another component of driving in Iran is that you are constantly being pleaded with by roadside vendors to buy their wares. People stand by the side of the road waving oranges, bananas, bottles of refreshment, and anything else they think they may entice you with. They are just as pervasive on this mountain road as they are on an expressway. They are not so much the danger, as are the purchasers, as they are prone to sudden stops, or driving at you from the opposite side of the road to negotiate for the bargain they have eyed.

If you are stopped in traffic, perhaps at a highway tollbooth or police checkpoint, they will descend to sell flowers, pillows, or food. From young children to the elderly, they all have something to sell.

Traffic chaos greets us as we descend the mountain and approach our destination. Several disorganized lanes converge to traverse a single lane bridge. After this bottleneck we are soon driving in excess of 100 km/h. Both sides of the road however are littered with debris and piles of rotting garbage. Many buildings are in disrepair.

After driving less than an hour along the coast we pull into a hotel/fast food parking lot to meet Javod. Masoud introduces him as a poet and his best friend. After a brief conversation Ali hops in Javod’s car and Masoud and I follow them down a series of twisted broken alleyways. Eventually we are driving down a wide boulevard that takes us to the Caspian Sea. It is the first time I see cows wandering about in a built up area. At this apparent dead end we turn left down a very rocky trail. This leads us to a rope gate and a wire-fenced property with more than a hundred meters of frontage on the seacoast. Within this compound, surrounded by newly planted trees is a two room newly constructed bungalow.

Several middle-aged men greet us. One of them is preparing freshly caught white fish on a concrete slab next to the house for our lunch. We have a tour of the property, taking time to skip stones into the sea and watch as fishermen tend to their nets.

Several middle-aged men greet us. One of them is preparing freshly caught white fish on a concrete slab next to the house for our lunch. We have a tour of the property, taking time to skip stones into the sea and watch as fishermen tend to their nets.

It is now time to move inside for tea and conversation. Javod opens a briefcase and pulls out a few sheaves of paper. He then begins to recite what I know to be poetry. Though I do not understand a word of the meaning, I feel the lyricism, flow and rhythm of his poetry as he speaks. Several men sit, entranced by his words.

His story is a tortured one, literally and figuratively. An engineer by profession, he is no longer permitted to practice his profession because of government restriction. Previously residing in Tehran, he was politically active and involved in student demonstrations at Tehran University last summer. As a result, he was arrested, questioned, beaten and tortured for his views. Well over six feet in height, his body is well proportioned. Signs of grey are appearing through his full head of dark hair. His face, though beginning to show the creases of middle age, displays a warmth and tenderness that I would thought uncharacteristic of someone who had suffered a state sponsored beating. But then, it is probably his openness that provoked the beating in the first place.

Apparently, this was the reason for his sudden move back to the coast. Wanting to reduce his profile to those who may be interested in his political activism, he has chosen to return, with his young family, to the community he grew up in.

How representative his story is of the tragedy of Iran. So rich with culture, emotion and expression, yet their citizens live in fear of their own government. So many people are afraid that they may speak the wrong words in the wrong place, allowing them to be overheard by someone who will betray them.

It is mid afternoon before we are sitting down for our lunch of fresh white fish, rice, yoghurt and bread. I can tell that Masoud wishes we had more time to enjoy an extended leisurely visit with his old friend. There are many stories that will have to be told on another day. We do linger, though, spending time visiting a family farm where kiwis, oranges and bananas grow.

As enjoyable as this is, our departure is now delayed to late afternoon, and we are several hours away from Tehran. After poignant goodbyes, we once again join the traffic of the coast, proceeding east on a jammed holiday route. Cows continue to be a concern, wandering aimlessly along the side of the road. Occasionally they graze on piles of discarded garbage.

Some additional albums of photos are available on my Picasa Website.

loom on either side. The road is busy, yet impatient drivers insist on attempting to pass. Overloaded vehicles crawling up the hill further reduces traffic speed while increasing everyone’s frustration level. Stone walls protect many of the roadside properties. Most of these walls are covered in painted advertising.

loom on either side. The road is busy, yet impatient drivers insist on attempting to pass. Overloaded vehicles crawling up the hill further reduces traffic speed while increasing everyone’s frustration level. Stone walls protect many of the roadside properties. Most of these walls are covered in painted advertising.  We pull into Gadchscar for a toilet break. The shaded ground is frozen, but mud is beginning to appear where the sun is shining. A police checkpoint is twenty metres ahead of where we stop. I observe them as they randomly motion oncoming traffic to pull over. We climb back into our vehicle and pull into traffic, but as soon as we approach the checkpoint we are ordered to the side of the road for inspection. The officer at the driver’s door demands my passport, while another officer opens my door. A brief discussion in Farsi ensues. It was later explained to me that the officer in temporary possession of my passport began to insist that I needed a permit to travel on this particular road. Masoud was able to deftly dissuade him of this opinion by pointing out that since I had a visa for Iran, and the road was in Iran, that I had all the permission I required. We continued on our journey.

We pull into Gadchscar for a toilet break. The shaded ground is frozen, but mud is beginning to appear where the sun is shining. A police checkpoint is twenty metres ahead of where we stop. I observe them as they randomly motion oncoming traffic to pull over. We climb back into our vehicle and pull into traffic, but as soon as we approach the checkpoint we are ordered to the side of the road for inspection. The officer at the driver’s door demands my passport, while another officer opens my door. A brief discussion in Farsi ensues. It was later explained to me that the officer in temporary possession of my passport began to insist that I needed a permit to travel on this particular road. Masoud was able to deftly dissuade him of this opinion by pointing out that since I had a visa for Iran, and the road was in Iran, that I had all the permission I required. We continued on our journey.  The trip through the gorge north from our tea break to Marzan Abad is relentless. It is the most dramatic highway I have ever experienced. The switchbacks are countless. Large rock faces hang over us. At times I feel that if I were permitted to stand in the middle of the road I could touch the gorge on either side.

The trip through the gorge north from our tea break to Marzan Abad is relentless. It is the most dramatic highway I have ever experienced. The switchbacks are countless. Large rock faces hang over us. At times I feel that if I were permitted to stand in the middle of the road I could touch the gorge on either side. Another component of driving in Iran is that you are constantly being pleaded with by roadside vendors to buy their wares. People stand by the side of the road waving oranges, bananas, bottles of refreshment, and anything else they think they may entice you with. They are just as pervasive on this mountain road as they are on an expressway. They are not so much the danger, as are the purchasers, as they are prone to sudden stops, or driving at you from the opposite side of the road to negotiate for the bargain they have eyed.

Another component of driving in Iran is that you are constantly being pleaded with by roadside vendors to buy their wares. People stand by the side of the road waving oranges, bananas, bottles of refreshment, and anything else they think they may entice you with. They are just as pervasive on this mountain road as they are on an expressway. They are not so much the danger, as are the purchasers, as they are prone to sudden stops, or driving at you from the opposite side of the road to negotiate for the bargain they have eyed.

Several middle-aged men greet us. One of them is preparing freshly caught white fish on a concrete slab next to the house for our lunch. We have a tour of the property, taking time to skip stones into the sea and watch as fishermen tend to their nets.

Several middle-aged men greet us. One of them is preparing freshly caught white fish on a concrete slab next to the house for our lunch. We have a tour of the property, taking time to skip stones into the sea and watch as fishermen tend to their nets.  We are now within 25 kms of Tafresh and climbing higher. The snow of the mountain appears to be travelling down to greet us. The road winds its way up, the twists and turns becoming tighter as we climb. The soil is often imbued with a green hue akin to the colour of a tarnished copper rooftop. We have reached the summit of our climb, and are now descending into Tafresh. Before entering the town, however, we are stopped at a police checkpoint. One officer with a holstered pistol motions us to the side of the road. He inspects the trunk and the back seat. Although I have my passport ready, I am not asked to produce it.

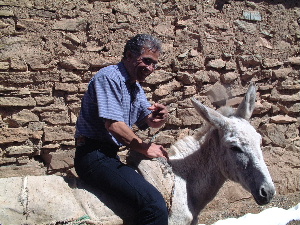

We are now within 25 kms of Tafresh and climbing higher. The snow of the mountain appears to be travelling down to greet us. The road winds its way up, the twists and turns becoming tighter as we climb. The soil is often imbued with a green hue akin to the colour of a tarnished copper rooftop. We have reached the summit of our climb, and are now descending into Tafresh. Before entering the town, however, we are stopped at a police checkpoint. One officer with a holstered pistol motions us to the side of the road. He inspects the trunk and the back seat. Although I have my passport ready, I am not asked to produce it. I do not know what to expect in the village itself, although I have heard much about it. The previous week some members of Masoud’s family had joked about whether or not I should be “allowed” to go to the village, perhaps fearing that I may find it too overwhelmingly rustic. Ultimately, nothing could be farther from the truth, as I was soon to discover. Most of the structures in this village, as in most of rural Iran that I have seen, are constructed out of yellow sand coloured brick or spread compound. This is just like so many of us in the west see on our television screens whenever Middle East villages are shown. Up close, though, touching it, I feel how weathered and impermanent it is.

I do not know what to expect in the village itself, although I have heard much about it. The previous week some members of Masoud’s family had joked about whether or not I should be “allowed” to go to the village, perhaps fearing that I may find it too overwhelmingly rustic. Ultimately, nothing could be farther from the truth, as I was soon to discover. Most of the structures in this village, as in most of rural Iran that I have seen, are constructed out of yellow sand coloured brick or spread compound. This is just like so many of us in the west see on our television screens whenever Middle East villages are shown. Up close, though, touching it, I feel how weathered and impermanent it is. As we enter the home of Masoud’s relatives, I am immediately impressed with the well cared for feel of the property. Yes, it is rustic. No material from Home Depot was used to construct this home. Farm animals are heard just behind the back wall of the main living quarters. But everything is cared for. Everything is in its place, and there seems to be a place for everything. This walled property is roughly twenty by thirty meters. Three buildings; a cookhouse, living quarters and a barn cover about 60% of this area. Different from most other structures in this village, they are built with stone and partially covered with whitewashed stucco.

As we enter the home of Masoud’s relatives, I am immediately impressed with the well cared for feel of the property. Yes, it is rustic. No material from Home Depot was used to construct this home. Farm animals are heard just behind the back wall of the main living quarters. But everything is cared for. Everything is in its place, and there seems to be a place for everything. This walled property is roughly twenty by thirty meters. Three buildings; a cookhouse, living quarters and a barn cover about 60% of this area. Different from most other structures in this village, they are built with stone and partially covered with whitewashed stucco.  I am soon introduced to several family members who are visiting during Narooz. Included are several young women between fifteen and thirty years of age. I am greeted by many warm, yet shy smiles. I remember the instructions given by Masoud before coming to Iran not to extend my hand to a woman, - to shake a woman’s hand only when it is offered. None is offered. Included in these introductions is Masoud’s Uncle, who immediately welcomes me in the traditional fashion with kisses on alternate cheeks three times. It is the first time I have felt the rasping of such grizzled whiskers against my face since hugging my grandfather goodnight as a child. This greeting feels very warm, open and accepting.

I am soon introduced to several family members who are visiting during Narooz. Included are several young women between fifteen and thirty years of age. I am greeted by many warm, yet shy smiles. I remember the instructions given by Masoud before coming to Iran not to extend my hand to a woman, - to shake a woman’s hand only when it is offered. None is offered. Included in these introductions is Masoud’s Uncle, who immediately welcomes me in the traditional fashion with kisses on alternate cheeks three times. It is the first time I have felt the rasping of such grizzled whiskers against my face since hugging my grandfather goodnight as a child. This greeting feels very warm, open and accepting.

The highlight of the day, however, is yet to come. I am speaking of the meal. A traditional feast served on the floor, with chicken kebabs, fresh bread, saffron rice many fine salads, and fresh yoghurt.

The highlight of the day, however, is yet to come. I am speaking of the meal. A traditional feast served on the floor, with chicken kebabs, fresh bread, saffron rice many fine salads, and fresh yoghurt.  In preparing to go, I ask if we may have a group picture. Everyone gathers, some more shyly than others.

In preparing to go, I ask if we may have a group picture. Everyone gathers, some more shyly than others. As we begin the return journey the air is clear. Unfortunately this condition does not last. In less than an hour, the thin brown line visible on the horizon grows ever larger. As we approach the city of Saveh, we are enveloped in this brown smudge. The reasons are obvious as we enter the city. Large factories are frothing black soot and old diesel buses are doing the same. Open fires can be seen on the side of the highway. North of Saveh we turn left to drive a few kilometres to a modern six-lane highway.

As we begin the return journey the air is clear. Unfortunately this condition does not last. In less than an hour, the thin brown line visible on the horizon grows ever larger. As we approach the city of Saveh, we are enveloped in this brown smudge. The reasons are obvious as we enter the city. Large factories are frothing black soot and old diesel buses are doing the same. Open fires can be seen on the side of the highway. North of Saveh we turn left to drive a few kilometres to a modern six-lane highway.